George ILIEV

Psychologists used to assume that attractive faces are remembered better and recognised more easily. It turns out they were wrong. Scientists in Jena, Germany, recently proved with experiments on test subjects that we remember unattractive faces better than attractive ones. (Read the details here.) Humans do prefer to look at a beautiful face longer, but the emotional influence actually reduces the precision of recognising this face later on.

Attractive faces also lead observers into another trap: false positives in recollection. We are more likely to think that we recognise an attractive face, even if we have never seen this face before.

All this makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. A positive experience for an animal can be finding abundant food or meeting a receptive sexual partner, while a negative experience can be dying at the claws of a predator. The positive experience can be enjoyed but only up to the point of satiation, after which life continues as normal. Whereas the negative experience may lead to a terminal outcome. Since the negative experience shapes to a bigger extent the survival chances of the animal, one would expect that evolution will remove from the gene pool those animals which do not prioritise avoiding unpleasant experiences. Thus remembering positive experiences "takes the back seat".

In a figurative way this principle applies to collecting customer feedback. Internet forums are full of irate customers who share at length their negative experience with a product or service, while much fewer stories are shared about a positive experience. It might be because customers don't remember the positive experiences as well as the negative ones. Or it might be a typically human example of selfless cooperation where irate customers try to alert fellow customers. Yet the parallel exists: a positive shopping experience can rarely be as indelibly printed in our mind as a negative experience would be. Just think of the feedback you would leave about a restaurant that gave you food poisoning.

Photo: Gisele Bundchen (Source: Wikipedia)

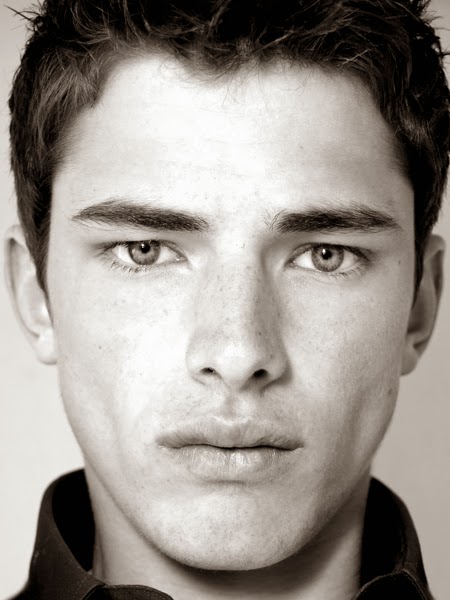

Photo: Sean O'Pry (Source: Wikipedia)